Beyond legal #18: data separation as a design strategy

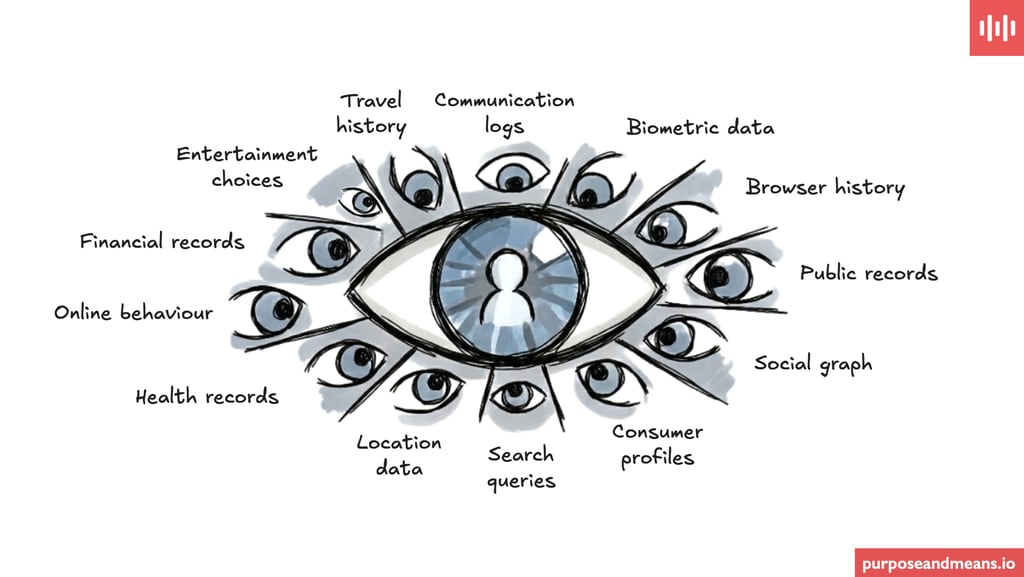

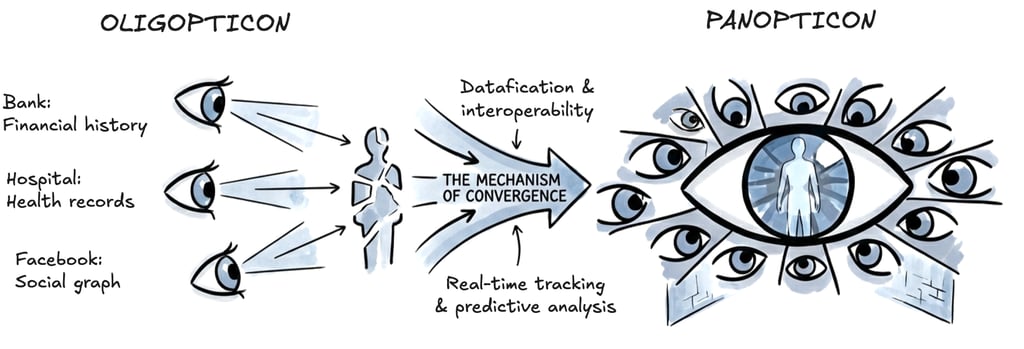

We often fear the single eye of 'Big Brother,' but a real threat to our fundamental rights is the architectural loss of data separation, which is allowing the distinct, partial gazes of the 'Oligopticon' to merge into a 360-degree Panopticon.

GRCDATA PROTECTION LEADERSHIPGOVERNANCE

Tim Clements

2/20/20268 min read

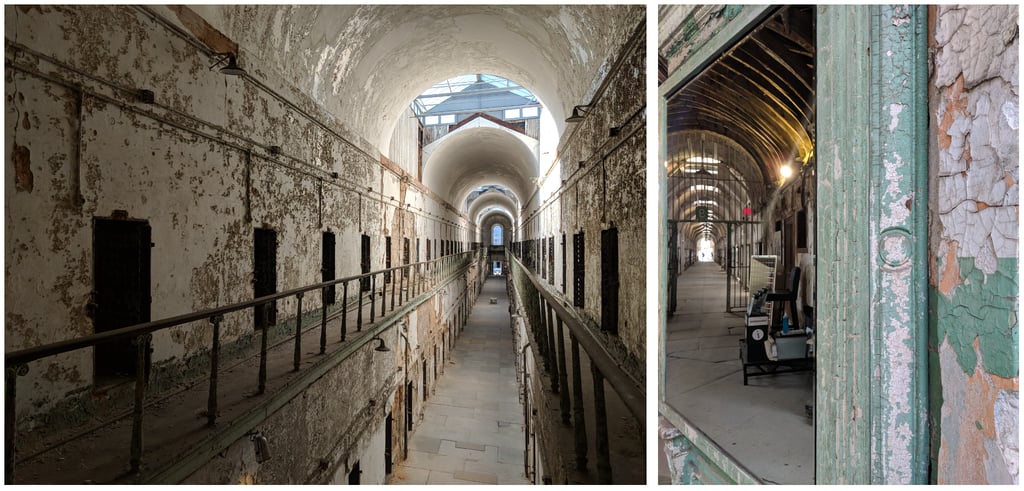

I occasionally see the use of the Panopticon as a metaphor to warn against the "Big Brother" state and the total surveillance of the digital age. The Panopticon is Jeremy Bentham’s 18th-century prison design where a single watchman observes all inmates, creating a state of permanent visibility.

In 2018 whilst attending a conference in Philadelphia I visited Eastern State Penitentiary, the former prison that at one time had Al Capone as a prisoner. It was a fascinating visit walking around the ruins and interestingly, key elements of the workings of the Panopticon were still in place. Aside from the obvious physical architecture, some of the mirrors that enabled the permanent visibility were still mounted on the walls. In the right-hand photo below you can see one such mirror (and obviously someone still gives them a good polish).

The Panopticon assumes a single, all-seeing eye. These days, the reality of the platform society is far more complex.

As I mentioned in my previous blog post, "Planting other trees in the forest," we can look to thinkers like Jose van Dijck to begin to understand the nature of modern surveillance. Van Dijck (building on concepts from the late Bruno Latour) talks much about the concept of the Oligopticon.

Unlike the Panopticon, which relies on a single observer, Van Dijck describes the Oligopticon as a system of "partial gazes." In this system, we are watched by many different entities, each seeing a narrow but precise view of us:

Your bank sees your financial history.

Your doctor sees your blood work.

Your social media platform sees your social graph.

When you first look at it, you might think that these "fragmented observations" are safer than a single Big Brother, but Van Dijck alerts us to the fact that these partial gazes are often interconnected.

In the platform society, these distinct oligopticons e.g., corporations, governments, and data brokers (to mention a few), constantly share and cross-reference data. The result is a distributed surveillance network where multiple partial views are joined together to form a comprehensive, holistic picture of the individual. This system is more pervasive than the Panopticon because it is everywhere, embedded in the sharing and "always on" culture in which many voluntarily participate, losing control over how their/our fragmented data is reassembled.

My point here is the danger is not just data collection, it is data connection.

Separating data can save lives

The danger of connecting these "partial gazes" is not theoretical. History has shown us that when data silos collapse and information is cross-referenced the result can be deadly

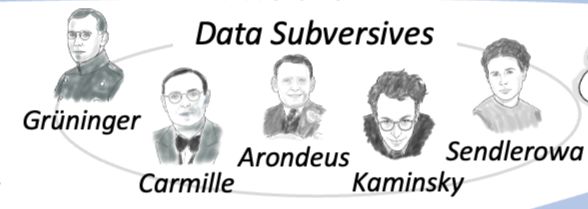

Last month, around the week of data protection day, I wrote a post on Linkedin about a group of "data subversives" who operated during WW2. These individuals realised that administrative data was no longer just bureaucratic. In the hands of an oppressor seeking a "comprehensive view" of the population, it was a weapon. They took action to address this:

Willem Arondeus led a group in Amsterdam that bombed the population registry in 1943. They understood that by destroying the physical records, they could prevent the Nazis from cross-referencing names with addresses and identities, effectively blinding the occupier.

René Carmille, a punch-card expert in France, programmed the census machines to physically jam or never punch "Column 11" - the column for religious affiliation.

Adolfo Kaminsky and Paul Grüninger manipulated identity documents. Kaminsky, a French master forger created false papers that allowed people to pass through the system unseen. Grüninger, a Swiss police commander, falsified dates on entry visas to save refugees who legally shouldn't have been there.

Irena Sendler in Poland took the opposite approach: she created a "shadow registry." While smuggling children out of the Warsaw Ghetto, she wrote their real names on slips of paper and buried them in jars under an apple tree. She separated their true data from the official system to preserve their future.

These "subversives" fought against the efficiency of the connected gaze. They understood that separating data saves lives. They fought to keep the views fragmented, preventing the regime from forming the "complete picture" necessary for total control. If you want to read more about these brave individuals, take a look at my interactive infographic about the origins and history of European data protection and privacy.

Today, we are rebuilding exactly what they tried to destroy. We are doing it not through military occupation, but through commercial integration.

In the graphic above, the risks are not just around data collection, but also data connection. When a bank, a social media company, or the state can cross-reference their data, the "narrow" view becomes a totalising one and when the walls between the silos dissolve then we can quickly be in a constitutional crisis.

M&A and partnerships

The move towards a more interconnected Oligopticon is driven by a market that seeks 360-degree customer views. When a bigtech company acquires a niche player, they are not just acquiring technology. They are buying a new "partial gaze" to add to their existing collection. A couple of examples in recent years caught the attention of the EDPB as they were concerned about the consequences of combining datasets that could negatively impact the fundamental rights of individuals by creating a profile of such depth that it would be impossible to escape:

Google & Fitbit: When Google acquired Fitbit, it sought to merge its "Search Oligopticon" (what you are interested in) with a "Health Oligopticon" (how your body functions).

Apple & Shazam: Similarly, Apple’s acquisition of Shazam allowed the device manufacturer to integrate granular listening habits into its broader ecosystem, effectively merging the hardware and software gaze with the cultural gaze.

Also be aware that contractual partnerships act as the "glue" between unconnected oligopticons. Data sharing agreements between apps, brokers, and advertisers mean that even without a merger, the "partial gaze" of one company is legally available to another.

And if you think this is too theoretical, here are some recent examples of what happens to our fundamental rights when the gazes connect.

1. The neighbourhood Panopticon: Amazon Ring (source)

The partial gaze: The private home security camera. Historically, Ring footage was seen as "private property," viewable only by the homeowner.

The connection: Amazon’s Ring created the "Neighbours" app and established contractual partnerships with over 2.000 police and fire departments.

The result: By aggregating millions of private views, Amazon created a massive, privately-owned surveillance network accessible by the state.

Fundamental rights impact: This erodes the Presumption of Innocence and Freedom of Assembly. It creates a society where simply walking down a street subjects you to a police lineup.

2. The welfare Panopticon: The SyRI legislation (source)

The partial gaze: Distinct government agencies holding separate data: water usage, tax returns, and vehicle registrations.

The connection: The Dutch government used SyRI (System Risk Indication) to link these disparate databases to algorithmically predict welfare fraud.

The Result: Innocent behaviours (e.g., low water usage combined with specific employment status) triggered fraud investigations. The state created a "glass house" for low-income citizens.

Fundamental rights impact: A Dutch court halted SyRI for violating Article 8 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (Right to Privacy). The court noted that the lack of transparency made it impossible for citizens to defend themselves against the "black box" of state power.

3. The biological Panopticon: Post-Roe period trackers (source)

The partial gaze: Femtech apps (like Flo or Clue) where users track menstruation cycles. A strictly medical/personal gaze.

The connection: Following the overturning of Roe v. Wade, data brokers and law enforcement began seeking access to this data to infer pregnancy status.

The result: The "medical gaze" of the app merges with the "punitive gaze" of the state. A missed period in an app, combined with geolocation data near a clinic, creates an evidentiary trail for criminal prosecution.

Fundamental rights impact: This threatens the Right to Health and Bodily Integrity. When health data becomes testimonial evidence against the user, individuals avoid seeking medical care, fearing self-incrimination.

4. The labour Panopticon: Workplace "bossware" (source)

The partial gaze: Traditional employment metrics (deadlines, clock-in times).

The connection: Tools like Hubstaff or Microsoft’s Productivity Score (initially) capture keystrokes, mouse movements, screenshots, and webcam feeds.

The result: The distinction between "working" and "thinking" is erased. The employer sees not just the output, but the process which intrudes upon the mental space of the worker.

Fundamental rights impact: This impacts Human Dignity and Labour Rights. It reduces the human worker to a data stream, eliminating the "unobserved space" necessary for creative thought and mental rest.

5. The living room Panopticon: Smart TVs and ACR (source)

The partial gaze: The television as a one-way display device.

The connection: Modern Smart TVs use Automatic Content Recognition (ACR) to identify what you are watching, and share that data with advertisers via contractual partnerships.

The result: The TV watches you back. It combines your viewing habits with your IP address (potentially linking to devices in your home) to build a profile of your political leanings and cultural interests.

Fundamental rights impact: This violates the Article 7 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (Respect for private and family life, home and correspondence). The home is traditionally the ultimate refuge from the public gaze. ACR technology turns the living room into a market research lab without explicit, informed consent.

Beyond Legal: Data separation as a design strategy

If we view the interconnected Oligopticon purely as a legal problem, what will happen if we're not careful is there'll be yet another legal solution such as "better contracts" or "more granular consent forms." This is where we need to move beyond compliance and towards architecture, and if you are familiar with the work of the Dutchman, Jaap-Henk Hoepman, then you may also be aware of his "little blue book" (free download) or Privacy Is Hard and Seven Other Myths: Achieving Privacy through Careful Design. Hoepman emphasises that data protection cannot be an afterthought. It must be engineered and he details (among many things) Separate as a fundamental design strategy.

Hoepman teaches us that we should process personal data in distributed datasets whenever possible, isolating distinct domains to prevent correlation:

Contextual integrity: By separating data, we respect the context in which it was given (healthcare vs. employment).

Risk reduction: If one database is breached, the attacker gets a slice, not the whole pie.

René Carmille and Willem Arondeus understood this intuitively in the 1940s. If the architecture of the system is designed for total connection, it can easily be used for oppression.

Today, the defence against the modern Panopticon cannot be left solely to lawyers. It requires Product Managers, Data Architects, and Engineers to embrace Hoepman’s strategy. From a data protection perspective we must design for unlinkability.

If we allow these gazes to merge through shared unique identifiers and interoperable databases, we lose more than our privacy. We lose the freedom to be different people in different places, a freedom that is essential to human dignity.

Purpose and Means is a niche data protection and GRC consultancy based in Copenhagen but operating globally. We work with global corporations providing services with flexibility and a slightly different approach to the larger consultancies. We have the agility to adjust and change as your plans change. Take a look at some of our client cases to get sense of what we do.

We are experienced in working with data protection leaders and their teams in addressing troubled projects, programmes and functions. Feel free to book a call if you wish to hear more about how we can help you improve your work.

Purpose and Means

Purpose and Means believes the business world is better when companies establish trust through impeccable governance.

BaseD in Copenhagen, OPerating Globally

tc@purposeandmeans.io

© 2026. All rights reserved.