Beyond legal #15: Data sovereignty and absolutism

Why absolutism fails unless the business is absolutist too — and what to do instead.

DATA PROTECTION MATURITYDATA PROTECTION LEADERSHIPGOVERNANCEHORIZON SCANNING

Tim Clements

1/5/20266 min read

In light of geopolitical events that have had a huge impact to many companies in recent years, especially 2025, I'm hearing these phrases in some data protection circles:

"We need sovereign data."

"We can’t use any US vendors."

"No US sub-processors."

"Localise everything."

"What are the EU alternatives."

...or similar words or phrases. It sounds decisive, but it also sounds a little bit like the old pattern I’ve been trying to move beyond in this series: theatre - lots of bold statements, documents and controls on paper and in theory, but very little operational capability when reality hits.

Data sovereignty is real. AI infrastructure sovereignty is real. Tightening rules are real. But the absolutist response - blanket bans and black-and-white policies, often fails to reflect the reality that an absolutist sovereignty stance only works if the business is absolutist too.

Absolutism is relatively easy on a personal level - I do try to practice this myself in the tech choices I make. I can decide not to use a specific platform, accept the inconvenience, and move on.

At a corporate level, absolutism is an operating model redesign. It touches everything:

market access and customer commitments

product roadmap and delivery speed

cost base, resilience, and talent

vendor ecosystem, security tooling, AI capabilities

support models, incident response, and audit evidence

If the business strategy remains “global scale, fast delivery, best-in-class tooling, predictable cost”, and the data and technology strategy becomes “sovereignty at all costs”, your entire business is at risk. You'll soon be dealing with:

exceptions,

workarounds,

shadow tooling,

and a fragmented architecture that increases risk through complexity.

Data sovereignty used to be discussed as a legal constraint: “where is the data stored?” That framing is now too small.

What’s happening instead is a strategic re-architecture of digital markets driven by three connected trends. I outlined the broader landscape (and the trends radar diagram below) in a recent blog post:

Data sovereignty & fragmented digital markets

Geography is becoming a design constraint. Digital markets are fragmenting into regional blocs with different rules and expectations. “Borderless” is no longer the default operating assumption.AI infrastructure as strategic sovereignty

AI infrastructure choices - cloud region, data centre location, chip/GPU dependency, managed AI services - have moved from “technical optimisation” into the realm of:sovereignty and national security expectations

resilience and outage tolerance

supply chain risk (including export controls and chip concentration)

ESG and energy footprint scrutiny

In other words: your infrastructure strategy is now a geopolitical and resilience strategy.

Tightening data sovereignty rules

More localisation mandates, more restrictions, more overlap between data protection and privacy, national security, and AI governance. Compliance is harder, and enforcement is more serious.

The response to these trends is not a ban list. The response is a capability.

Try this: The sovereignty alignment test

If you want to adopt an absolutist sovereignty approach (e.g. “no US sub-processors, ever”), run this test first:

Is my company also willing to adopt the business posture that comes with it?

Market: Are we willing to lose deals/markets where sovereignty isn’t achievable today?

Cost: Are we willing to pay for duplicated regional stacks and assurance overhead?

Product: Are we willing to accept slower delivery and regional feature divergence?

Vendors: Are we willing to reduce our choice of tools - especially for AI, security, and observability - until local alternatives emerge or mature?

Resilience: Are we ready for the complexity risk created by fragmentation (more moving parts = more failure modes)?

Talent: Can we staff, operate, and secure multiple regional architectures properly?

Roadmap: Do we accept this as a multi-year transformation rather than a policy announcement?

If your leadership can’t say “yes” to those trade-offs, an absolutist sovereignty policy is not a strategy. It’s a future exception register.

And exceptions are not free. They become risk debt, often undocumented, usually poorly governed, and guaranteed to resurface when you least want them to, e.g. during an incident, or audit to name a couple of examples.

“Risk-based approach” does not mean eliminate all risk

A risk-based approach is frequently misunderstood in sovereignty conversations. It does not mean:

“remove all risks at any cost”

“choose the most restrictive option by default”

“treat any transfer or US linkage as automatically unacceptable”

It means:

identify risks in context,

implement appropriate controls (technical, organisational, legal),

accept and manage residual risk consciously,

document decisions and review them as things change.

An absolutist approach can have severe business impact: cost overruns, reduced capability, delivery delays, and ironically, a weaker security posture because the architecture becomes fragmented and harder to operate safely.

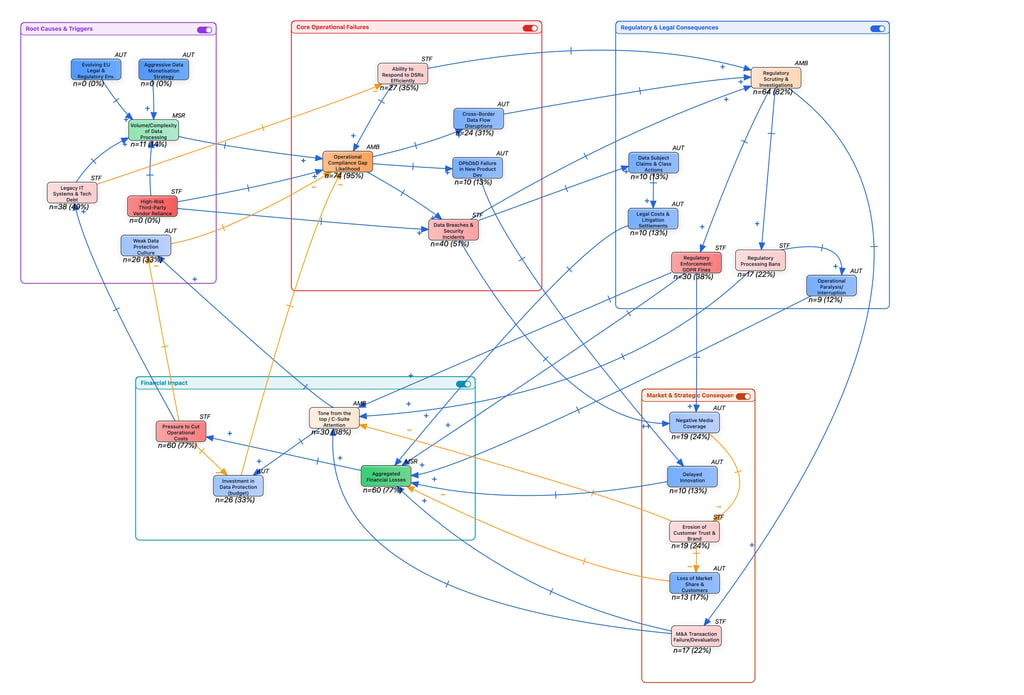

If you want a visual reminder that risk behaves like a system, where decisions create ripple effects and feedback loops, this is exactly why I built my causal loop diagram:

See this recent blogpost that explains the diagram.

Sovereignty without the drama

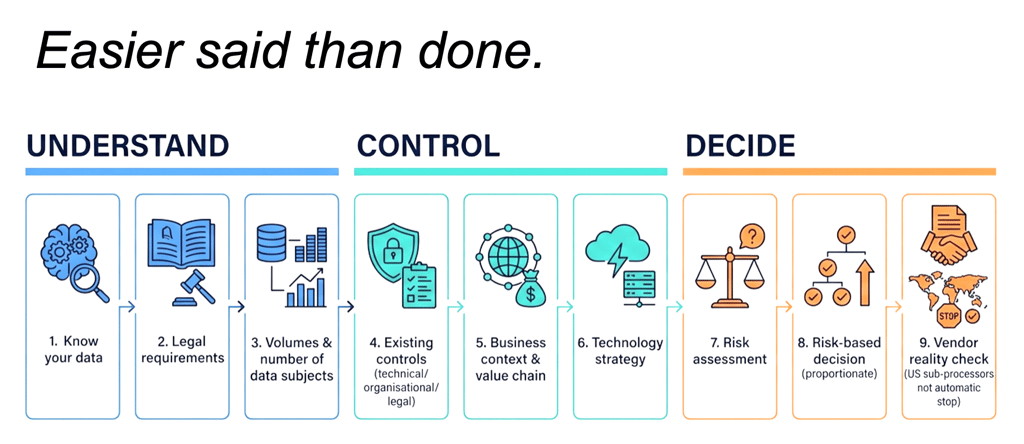

Below is my suggested and pragmatic approach. In line with everything I've said in this 'beyond legal' blogpost series, it’s intentionally cross-functional: CISO/CTO/CPO, plus procurement, architecture, engineering, data governance, and risk.

Step 1: Know your data (what personal data is involved, if any?)

Before debating processors, sub-processors or regions, map:

what personal data exists and where

sensitivity (special category, children, location, biometrics, etc.)

purpose and value-chain dependency

overlooked personal data: logs, identifiers, telemetry, analytics events

if AI is involved: training data, fine-tuning data, prompts/outputs, RAG datasets, evaluation datasets

If you have a RoPA or an expanded data map and it's all up-to-date, this will help facilitate this step.

Outcome: sovereignty conversations become data-class specific, not ideology-driven.

Step 2: Make yourself aware of the legal requirements

Based on the data you're processing, you need clarity on:

which jurisdictions apply (data subjects, entities, processing locations)

sector rules (finance, health, telecoms, public sector procurement)

what is hard localisation vs “allowed with safeguards”

AI-specific obligations where relevant (model lifecycle constraints, transparency, logging)

Outcome: you begin treating sovereignty as a documented set of constraints.

Step 3: Quantify data volumes and data subjects

how much data (and growth rate)?

categories of, and volumes of data subjects?

what is the concentration (one dataset vs. spread across systems)?

what’s the worst-case exposure scenario?

Outcome: you can prioritise. Not everything needs the same approach.

Step 4: Assess controls already in place (technical, organisational, legal)

Sovereignty is not only where the infrastructure sits. Controls often matter more:

Technical

encryption in transit/at rest

key management model (and who holds keys)

segmentation and tenant isolation

access governance (PAM/JIT/MFA/least privilege)

monitoring, logging, anomaly detection

tokenisation/pseudonymisation

backup and DR geography controls

restricting admin/support access paths where feasible

Organisational

ownership and stewardship

change control for data flows and AI model lifecycle

incident response readiness across regions

supplier monitoring discipline

Legal

DPAs and R&Rs

sub-processor transparency and approval workflow

audit/assurance rights and evidence expectations

cross-border transfer mechanisms where relevant

Outcome: you discover where risk can be reduced without knee-jerk bans.

Step 5: Nature of business and value chain information needs

This really is the 'beyond legal' heart of sovereignty. Ask:

what information must flow for fraud, security operations, support, analytics, product improvement?

where will localisation break core workflows?

what is the commercial reality (public sector, regulated customers, procurement gates)?

Outcome: sovereignty posture becomes aligned with business strategy, not clashing with it.

Step 6: Choose your approach(es)

A practical way to avoid absolutism is to define one or more sovereignty approaches by data class and workload (for example):

"Sovereign-by-necessity"

Highly regulated/high-risk datasets and workloads. Localise and ring-fence with strong assurance."Multi-sovereign modular"

Regional data planes with governed cross-region capabilities (such privacy-preserving patterns, minimisation, aggregation). This is where some multinationals end up."Global with controls"

Low-risk datasets/workloads where global processing is acceptable with safeguards and documented residual risk.

Outcome: you stop trying to force one rule onto all processing and start designing for reality.

Please note that Sovereign‑by‑necessity, multi-sovereign modular and global with controls are not formal legal categories.

US sub-processors are not automatically a show-stopper

“AWS or Google anywhere in the chain = stop.”

A US-based processor or sub-processor may increase certain risks (including government access considerations). But it is not automatically a decisive conclusion without understanding:

what data is involved (and sensitivity)

what the sub-processor actually does, i.e. the actual processing services it provides to you. And this is where I see too much alarmism. Just because a controller or processor lists a US vendor in their privacy policy, it requires deep understanding in your unique business context

what access paths exist (including support)

what safeguards exist (encryption, key control, segmentation)

what residual risk remains, and whether it is acceptable for this dataset and business purpose

Sometimes the answer will be: localise.

Sometimes the answer will be: proceed with strong safeguards and documented residual risk.

Either can be defensible. The indefensible position is making the decision before understanding the data and the controls.

Closing: build sovereignty capability

The 'beyond legal' lesson here is simple:

Sovereignty is governance (board-level direction and risk appetite).

Sovereignty is architecture (modular, multi-region, control-rich).

Sovereignty is business strategy alignment (markets, cost, capability trade-offs)

Purpose and Means is a niche data protection and GRC consultancy based in Copenhagen but operating globally. We work with global corporations providing services with flexibility and a slightly different approach to the larger consultancies. We have the agility to adjust and change as your plans change. Take a look at some of our client cases to get sense of what we do.

We are experienced in working with data protection leaders and their teams in addressing troubled projects, programmes and functions. Feel free to book a call if you wish to hear more about how we can help you improve your work.

Purpose and Means

Purpose and Means believes the business world is better when companies establish trust through impeccable governance.

BaseD in Copenhagen, OPerating Globally

tc@purposeandmeans.io

© 2026. All rights reserved.